Introduction

Materials and Methods

Experimental setup and treatment

Sample preparation and primary metabolite profiling

Statistical analysis

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

Introduction

Increasing meat consumption with economic growth is leading to the greater requirement of livestock feeds year by year. Despite of more than 80% of the self-sufficiency of coarse fodder for livestock feeding, high quality grasses including sudangrass just account for less than 30% (MAFRA, 2022). Sorghum-sudangrass hybrid has been known for excellent biomass yield and low maintenance requirements for feedstock production (Pedersen, 1996; Reddy et al., 2005), and is a subtropical crop to require the relatively higher temperature for suitable growth and high nutritional value (Choi et al., 2022). The production of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid for livestock (meat and dairy cattle) feed could be secured at summer season and usually takes 90 - 120 days after sowing for the harvest (Choi et al., 2017). Additionally, sorghum-sudangrass hybrid is resistant against abiotic stresses such as drought and high temperature, and is the higher yield crop compared to other forage crops (Yoon et al., 2007; Uzun et al., 2009).

Nitrogen (N) is an essential macronutrient substantially required for plant structure and function. N is directly involved in plant macromolecules including nucleotides, hormones, chlorophyll and amino acids, and thus constitutes up to 2 and 16% of plant dry biomass and proteins, respectively (Frink et al., 1999). N application obviously promotes the biomass yield of sorghum (Afzal et al., 2013) and sorghum-sudangrass hybrid (Beyaert and Roy, 2005), and thus the development of an optimal N management can allow sorghum-sudangrass harvest more than two times. In context of primary metabolism, N greatly perturbs an abundance in primary metabolites, which indicate that increasing N conditions resulted in large accumulation of free amino acids and marked reduction in soluble carbohydrates (Rufty et al., 1988; Urbanczyk-Wochniak and Fernie, 2005; Tilsner et al., 2005).

Despite many reports on fertilization efficiency and biomass production of annual sorghum-sudangrass hybrid, there is still necessary for extending our knowledge in terms of nitrogen-affected primary metabolites. Therefore, it is necessary to know whether difference levels of N application affect primary metabolism, and the objective of the current study was to identify a variation of targeted primary metabolites under various nitrogen fertilization rates at heading and harvesting stages of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid.

Materials and Methods

Experimental setup and treatment

This work was performed at the experimental field in Chungbuk Agricultural Research and Extension Service (CARES) from May to August, 2022. Seeds of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid (cv. SX17, heading type) were strip-sown with a furrow of 50 cm (width, 40 kg ha-1) at 10th May, 2022. Experimental plot was arranged with a randomized block design (60 m2 per treatment, 3 replications). The standard fertilization was 175 kg N ha-1, 150 kg P ha-1 and 150 kg K ha-1, and N was split with three times as a rate of 40 (basal): 30 (20 days after sowing, DAS): 30% (45 DAS), and total requirement of P (P2O5) and K (K2O) were applied as a basal fertilization. To develop variable N application, N dose was divided into four different levels: 0%, 100% and 200% to the standard N application rate. An experimental soil was analyzed according to NAAS method (NAAS, 2010). The pH and EC were measured with pH/EC meter (sampled soil : ddH2O = 1:5). The soil total carbon (dried soil) was measured C/N analyzer (vario Max CN Element Analyzer, Elementar GmbH, Germany), and transformed to organic matter with multiplying by 1.724. An available phosphate extracted with Lancaster method was measured with UV-Spectrometer (720 nm, UV 1900i, Shimadzu, Japan). The cations (5 g of dried soil) were analyzed with ICP (GBC, Intergra XL. Australia) after an extraction (25 mL of 1 N CH3COONH4, pH 7.0).

Sample preparation and primary metabolite profiling

The shoots (leaf + stem) of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid (30 × 30 cm) were taken at harvest stage from different nitrogen fertilization rates, immediately divided into leaves and stems after washing with deionized-distilled water, and stored at -80°C for further analysis. Primary metabolites were analyzed according to the previous report (Kim et al., 2016). One hundred milligrams of powdered samples were extracted with 1mL of methanol : water : chloroform (2.5:1:1, v/v/v) solution, and ribitol (60 µL, 0.2 mg mL-1) solution was used as an internal standard (IS). Extraction was performed at 37°C at a mixing frequency of 1,200 rpm for 30 min using a Thermomixer Compact (Eppendorf AG, Germany). The extracts were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 3 min. The polar phase (0.8 mL) mixed with 0.4mL water was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 3 min. The methanol/water phase was dried in a centrifugal concentrator (CC-105, TOMY, Tokyo, Japan) for 2 h, followed by a freeze dryer for 16 h. MO-derivatization was performed by adding 80 µL of methoxyamine hydrochloride (20 mg mL-1) in pyridine and shaking at 30°C for 90 min. TMS-esterification was performed by adding 80 µL of MSTFA, followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min. GC-TOF-MS was performed using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent, Atlanta, GA, USA) coupled to a Pegasus HT-TOF mass spectrometer (LECO, St. Joseph, MI). Each derivatized sample (1 µL) was separated on a 30 cm × 0.25 mm I.D. fused-silica capillary column coated with 0.25 µm CP-SIL 8 CB low bleed (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The split ratio was set to 1:25. The injector temperature was 230°C, and a flow rate of helium gas through the column was fixed with 1.0 mL min-1. The temperature was set up as follows: initial of 80°C for 2 min, followed by an increase to 320°C at 15°C min-1 and a 10 min hold at 320°C. The transfer line temperature and ion-source temperature were 250 and 200°C, respectively. The scanned mass range was 85–600 m/z, and the detector voltage was set to 1700 V. ChromaTOF software was used to support peak findings prior to quantitative analysis and for automated deconvolution of the reference mass spectra. NIST and in-house libraries for standard chemicals were utilized for compound identification. The calculations used to quantify the concentrations of all analytes were based on the peak area ratios for each compound relative to the peak area of the IS.

Statistical analysis

Difference in metabolites (N100 or N200 to N0) was analyzed by T-test (RStudio 4.2.2). The selected metabolites (Fig. 2) to compare the difference among treatments were subjected to an ANOVA test, and further analyzed using LSD test if p < 0.05 (n = 3, RStudio 4.2.2). Additionally, the principal component analysis (PCA) was also performed to identify the association between nitrogen fertilization and metabolites (RStudio 4.2.2).

Results and Discussion

Soil chemistry was measured before and harvest of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid plants (Table 1). Soil parameters except electrical conductivity (EC) and organic matter (OM) were not differed from both time points and nitrogen treatment. EC was significantly decreased in all treatments, which is considered due to nutrient uptake by sorghum-sudangrass hybrid plants, while organic matter (OM) showed a tendency of obvious increase as a result of compost application. Furthermore, soil pH, available P2O5 and exchangeable Ca were higher compared to the recommendation.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the experimental soil used in this study.

| Time |

N (kg ha-1) |

Soil series |

Soil texture |

pH (1:5) |

EC (dS m-1, 1:5) |

T-N (g kg-1) |

OM (g kg-1) |

Av. P2O5 (mg kg-1) | Exch. cations (cmolc kg-1) | ||

| K | Ca | Mg | |||||||||

| Before | - | Seogcheon | Sandyloam | 7.3 a | 0.68 a | 0.14 b | 16.2 c | 740ns | 0.27 a | 7.9 b | 1.5 c |

| Harvest | 0 | - | - | 7.4 a | 0.37 b | 0.15 ab | 28.5 a | 766 | 0.27 a | 8.7 a | 1.9 a |

| 100 | - | - | 7.1 b | 0.30 c | 0.14 ab | 22.0 b | 761 | 0.26 a | 7.7 b | 1.7 b | |

| 200 | - | - | 7.0 c | 0.40 b | 0.17 a | 27.6 a | 785 | 0.24 b | 6.8 c | 1.5 bc | |

| Optimum1 | - | Sandyloam- Siltloam | 6.0 - 6.5 | - | - | 25 - 30 | 200 - 250 | 0.45 - 0.55 | 5.0 - 6.0 | 1.5 - 2.0 | |

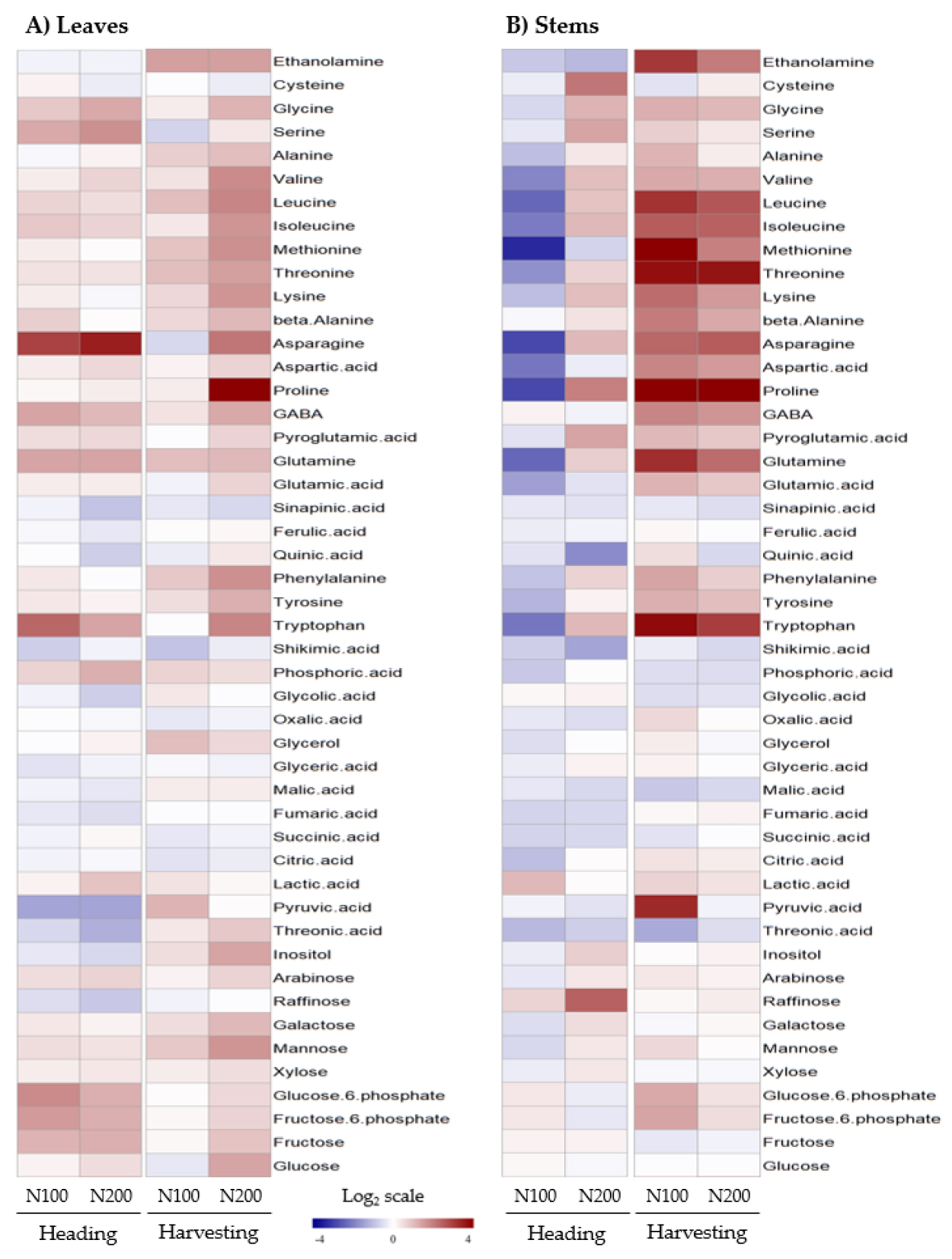

Metabolic profiling of sorghum-sudangrass hybrid leaves and stems using GC-TOF-MS identified 48 metabolites. To elucidate the accumulation patterns under different N fertilization levels at heading and harvesting stages, normalized numerical methods were employed, and created a heatmap (Fig. 1). Despite similar biomass production between N levels except N0 (no significance at p < 0.05), the heatmap revealed that increasing N fertilization showed a tendency of up-regulated sugars and amino acids but down-regulated organic acids and derivatives. Notably, N fertilization led to a significant accumulation of monosaccharides such as glucose (p < 0.05), fructose (p < 0.01), glucose-6-P (p < 0.01), fructose-6-P (p < 0.01), and xylose (p < 0.01). in leaves at heading stage. Several important sugars involved in C metabolism were significantly upregulated by high N fertilization (Zhen et al., 2016), and this is consistent with our result observed in leaves and stems under increasing N fertilization (Fig. 1). On the other hand, an increasing rate of N application led to a decrease in sugar concentration (Chung et al., 2010; Shi et al., 2019). This suggests that an abundance in sugars could be varied with species, and thus we propose that the level of N fertilization employed in this study influences an abundance of sugar pools, which could be effective for reproductive growth. Another interesting thing is an accumulation of raffinose, revealing greater abundance in stems at both time points (1.6 - 5.7-fold greater than N0, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1). Genes involved in raffinose synthesis, one of source-sink mobile molecules, was highly upregulated during floral initiation (McKinley et al., 2022). Additionally, raffinose can supplement sucrose as phloem-mobile forms, supporting non-photosynthetic tissues and organs (Madore, 2001). Therefore, our result demonstrates the evidence that sorghum-sudangrass hybrid predominantly accumulates a raffinose in stems as a storage.

An increasing N fertilization had an obvious effect on an abundance in amino acid in stems at harvesting stage. In terms of relative concentration, N-rich amino acids such as glutamine (C5N2) and asparagine (C4N2) in stems at harvesting stage significantly accumulated 3.3 (log2 scale, p < 0.05)- and 2.4 (p < 0.05)-fold greater and in N100 and 2.3 (p < 0.01) and 2.6 (p < 0.05)-fold higher in N200 compared to N0, respectively. N-rich amino acids such as glutamine and asparagine play key roles in assimilation, recycling, translocation and storage of nitrogen (Sebastia et al., 2005; Hildebrandt et al., 2015), and high N fertilization accelerated the accumulation of N-rich amino acids (Zhen et al., 2016), similar to our observation. Our findings imply that most of amino acids under N fertilization shows a tendency of preferential accumulation in stems at harvesting stage although they are evidently greater in leaves. In addition, integrated C/N metabolism by greater concentration of N-rich amino acids could be improved by N fertilization, promoting growth and development. We propose that C/N metabolism in a sorghum-sudangrass hybrid plant is precisely regulated by N availability like the level of N fertilization.

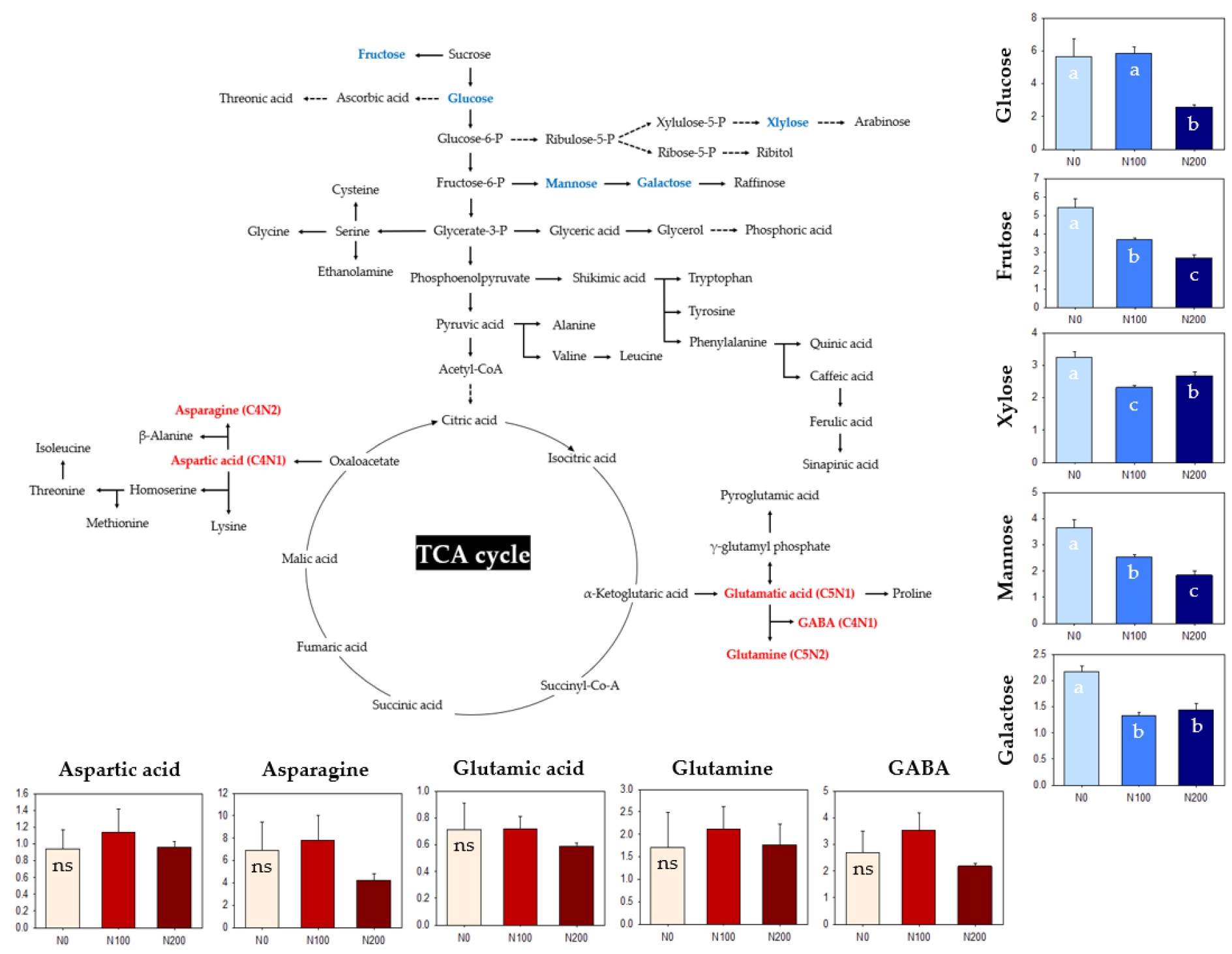

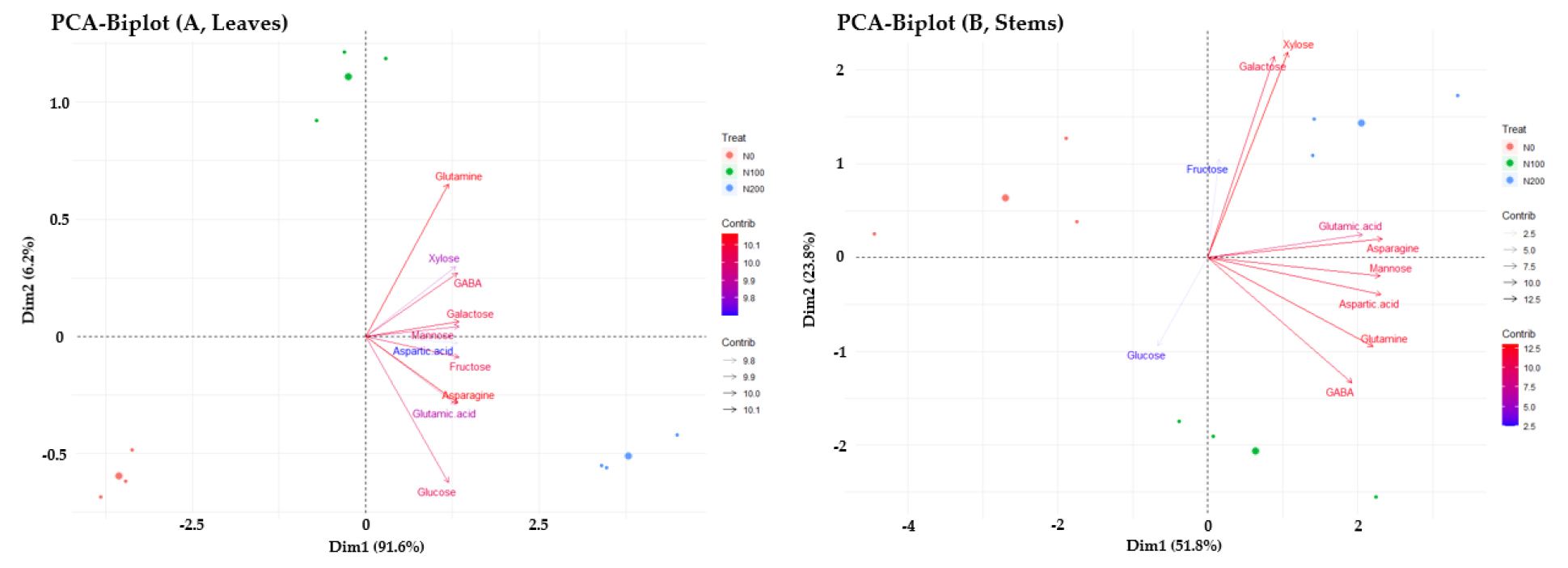

Based on metabolite profiling results, selected metabolites were further analyzed (Fig. 2). Sugars and amino acids were evidently perturbed by nitrogen levels, and metabolite abundance was analyzed by tissues, growth stages, and nitrogen levels. Less N fertilization significantly promoted the accumulation of monosaccharides in stems compared to increasing N fertilization groups (N100 and N200). In contrast, the ratio of selected amino acids did not differ with the level of N fertilization. Despite a constant ratio (stems/leaves) of amino acids, N-rich amino acids were more abundant in the stems: glutamine (log2 scale, 2.3 - 3.3), GABA (1.7 - 1.9), and asparagine (2.4 - 2.6). Principal component analysis was performed to understand the association between selected metabolites and N fertilization, and the projections with two principal components from the leaf and stem were visualized (Fig. 3). Most selected metabolites were closely associated with N fertilization, with variables trending towards N200 rather than N100. Fructose, mannose, galactose, and aspartic acid were primarily responsible for PC1 in the leaf, while mannose, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and asparagine were substantially related to PC1, and fructose, galactose, and xylose to PC2 in the stem.

Overall, our study revealed that increasing nitrogen fertilization significantly impacted the variation in sugars and amino acids. The results suggest a strong association between nitrogen fertilization rates and metabolites, particularly monosaccharides and higher N-rich amino acids.

Conclusions

Metabolic profiling revealed 48 identified metabolites in leaves and stems. Higher nitrogen fertilization up-regulated sugars and amino acids. Monosaccharides were accumulated in leaves with higher nitrogen at heading stage, while raffinose was abundant in stems. Glutamine and asparagine as an amide were greater in stems at harvesting stage. Despite a consistent ratio (stems/leaves), nitrogen-rich amino acids were more abundant in stems. Principal component analysis highlighted associations between selected metabolites and nitrogen fertilization. In conclusion, different levels of nitrogen fertilization were significantly responsible for sugar and amino acid pools.