Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study site

Initial soil properties before Kimchi cabbage cultivation in 2021 and 2022 experimental years

Treatment application and experimental design

Planting Kimchi cabbage and agronomic practices

Rainfall distribution during the 2021 and 2022 experimental years

Soil data collection

Yield data collection

Statistical data analysis

Results and Discussion

Effects of fertilizers on Kimchi cabbage yield

Nitrogen content and uptake of Kimchi cabbage

Soil electrical conductivity

Soil N (NH4+ and NO3-) concentration

Soil chemical properties after Kimchi cabbage harvest

Conclusions

Introduction

Kimchi cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) is an important crop in South Korea, serving as a major side dish in many cuisines (Wi et al., 2020). It has increased in demand, especially post-COVID, because of its immune enhancing properties (Go et al., 2022). Though high in demand, farmers growing Kimchi cabbage must be tactful about the natural and managed production factors such as temperature, soil moisture, soil fertility among others that affect productivity and profits (Hwang et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2015; Son et al., 2015). It is one of the major crops cultivated in the mountainous, highland region of the Gangwon State Government, due to favourable temperatures in the area (Hong et al., 2018). To increase productivity, it is the usual farmer practice to apply excessive rates of conventional fertilizer, though the Rural Development Administration (RDA) elaborates standard rates to apply for various crops (Kim et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022). Over the years, research has outlined the negative potential and real environmental impacts of continuous conventional fertilizer use. The year after year intensive cultivation of Kimchi cabbage with conventional fertilizer triggers residual nutrient build-up in soil; consequent excessive losses of nutrients from the soil system into the atmosphere as greenhouse gases and into water bodies, causing eutrophication; and reduced crop responses to fertilizer (Ozer, 2003; Rose and Bowden, 2013). As a result, conventional fertilizer applications do not often warrant desired increases in Kimchi cabbage yield in the region. On the other hand, other studies have found that optimizing fertilizer use while protecting the environment may be achieved by the application of slow release fertilizer (SRF) to annual Kimchi cabbage cropping systems (Bahar et al., 2019; Wesolowska et al., 2021). Unlike conventional fertilizer, which readily releases most of its nutrient after application, SRF slowly releases nutrients over a span of time, allowing nutrient release to synchronize with critical crop nutrient demand periods (Geng et al., 2015). Though SRF could be more expensive than equal amounts of conventional fertilizer, it is applied one-time during the cultivation period and as such does not incur extra labour cost for split application (Jat et al., 2012). SRF may reduce the total amount of fertilizer required for application and increase fertilizer use efficiency, which may enhance economic efficiency as well (Gao et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2016). Its mode of action reduces the build-up of residual nutrients in the soil and potential consequent environmental effects (Timilsena et al., 2015). Sikora et al. (2020) observed a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emission in Kimchi cabbage fields, following the application on 108 kg ha-1 N through SRF, compared to the same rate through conventional fertilizer. Though the benefits of SRF have been widely documented elsewhere, there is scanty information on how it would affect the productivity of Kimchi cabbage and the environment in the Gangwon State Government in order to make recommendations to farmers. This paper presents the early part of an on-going research that seeks to explore all the facets to ensuring sustainable management of Kimchi cabbage cropping systems using slow release fertilizer. It focuses on evaluating the Kimchi cabbage yield and the soil chemical properties following SRF in the first two years of application.

Materials and Methods

Study site

The studies were conducted during the Kimchi cabbage growing seasons of 2021 and 2022 at 2 different field locations in the Highland Agriculture Research Institute inside the Gangwon State Government. The year 2021 experiment was performed in the sloping area with sandy loam soil, while the year 2022 experiment was in the flat area with loam soil.

Initial soil properties before Kimchi cabbage cultivation in 2021 and 2022 experimental years

Five soil samples were collected randomly with an auger at 15 cm depth from each field, for physico-chemical analysis before the start of the experiments. Plant materials at the top 1 cm of the soil were slashed off to prevent overestimation of soil properties. The samples were composited, mixed thoroughly and sifted through a 2 mm sieve before analysis. The soil was analysed for pH, electrical conductivity (EC), organic matter (OM) content, ammonium nitrogen concentration (NH4-N), nitrate nitrogen concentration (NO3-N), available phosphorus pentoxide concentration (P2O5) and exchangeable cations [potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca)]. Table 1 shows the soil properties before the start of the experiments in 2021 and 2022.

Table 1.

Initial physico-chemical properties of the soil before experimental set-up in 2021 and 2022.

| Year | Treatment |

pH (1:5) |

EC (dS m-1) |

OM (g kg-1) | NH4-N (mg kg-1) | NO3-N (mg kg-1) | Av. P2O5 (mg kg-1) | Exch. cations (cmolc kg-1) | ||

| K | Mg | Ca | ||||||||

| 2021 | CF | 6.9 | 0.21 | 18 | 7 | 8 | 482 | 0.53 | 1.5 | 8.0 |

| SRF | 6.6 | 0.20 | 16 | 7 | 10 | 422 | 0.50 | 1.4 | 6.6 | |

| Control | 6.6 | 0.23 | 17 | 8 | 10 | 623 | 0.67 | 1.4 | 7.2 | |

| 2022 | CF | 6.0 b† | 0.30 | 41 | 4 | 2 b | 238 | 0.87 | 1.1 | 4.3 |

| SRF | 6.1 a | 0.27 | 39 | 6 | 4 a | 255 | 0.87 | 1.2 | 4.5 | |

| Control | 6.0 c | 0.20 | 43 | 5 | 2 b | 238 | 0.83 | 1.1 | 4.3 | |

| Optimum range | 6.0 - 6.5 | < 2 | 25 - 35 | 50 - 200 | 350 - 450 | 0.65 - 0.80 | 1.5 - 2.0 | 5.0 - 6.0 | ||

All soil parameters were analysed using the standard analysis methods of the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (NAAS, 2011). Soil pH was determined with a pH meter at a soil to distilled water ratio of 1:5 and the values were multiplied by a dilution factor of 5. Soil carbon concentrations were determined with an elemental analyser (Orion Versa Star, Thermo, USA) and then converted to soil organic matter values by multiplying it by a factor of 1.75. Soil NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations were measured by KjelMaster system (K-375, Buchi, Switzerland). Soil available phosphorus concentration was calorimetrically quantified at 720 nm wavelength with the UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Lambda 365, Perkin Elmer, USA). Exchangeable cations (Ca, K and Mg) in the soil were extracted with 1 N mono-ammonium acetate and measured with inductively coupled plasma. Optimal soil property ranges recommended by NIAS (2022) for Kimchi cabbage cultivation in Korea, were used to rate the soils before the start of the experiments.

Treatment application and experimental design

Three treatments including: conventional fertilizer (CF), slow release fertilizer (SRF) and no fertilizer control were applied in 2021 and 2022 by the broadcasting method. The two fertilizers were applied at N:P2O5:K2O rates of 132:60:60 kg ha-1 in 2021, which was the recommendation provided by the fertilizer company. The rates were increased to 236: 108: 108 kg ha-1 in 2022, following the standard N recommendation by National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (NIAS, 2022). The CF was applied as a mixture of urea, fused phosphates and muriate of potash (KCl). Urea and muriate of potash were split-applied at one week before Kimchi cabbage transplant at 83 and 39 kg ha-1 N and K; and the remainder of the full rates were applied in the third week of July in both years. However, the full rate of P was applied at one week before transplant in both years. Full NPK rates of the SRF were applied one week before transplanting in both years. Treatments were replicated three times in each field in both experimental years in randomized complete block designs (RCBD). Each treatment plot measured 15 m2 in 2021 and 14 m2 in 2022.

Planting Kimchi cabbage and agronomic practices

During land preparation, previous vegetation cover was ploughed in the soil after initial soil sampling. The land was treated with herbicide to control weeds before transplanting Kimchi cabbage. Four weeks old Kimchi cabbage seedlings were transplanted to the field at a planting distance of 70 cm × 35 cm on 06/02/2021 and 06/10/2022 in both experimental years. After transplanting, the fields were manually weeded at 30-day intervals to control weeds. Pesticide was applied at the observation of signs and symptoms of pests. In both years, the cabbage was harvested two months after transplanting. After cabbage harvest, residues were left on the soil surface to decompose. Grass weeds succeeded the residue cover after decomposition.

Rainfall distribution during the 2021 and 2022 experimental years

There were six rainfall events and nine rainfall events during Kimchi cabbage cultivation period in 2021 and 2022 respectively. Total amount of rainfall received during the period was 270 mm in 2021 whereas that received in 2022 was 589 mm. The rainfall distribution in 2021 was quite steady while that in 2022 was rather erratic with relatively larger amounts received close to the end of the 2022 growing period. Fig. 1 shows the rainfall amounts and distribution throughout the Kimchi cabbage cultivation periods in both years.

Soil data collection

Five soil samples were collected randomly from each plot at 15 cm depth at two-week intervals for six times in 2021 and six times in 2022. Samples from each plot at each sampling time were composited and analysed for the dynamics in EC, NH4-N and NO3-N during a cultivation period. After Kimchi cabbage harvest, the plots were analysed again for pH, EC, OM, NH4-N, NO3-N, available P2O5, K, Mg and Ca.

Yield data collection

Ten cabbage heads were harvested randomly from the middle of a plot, avoiding the borderlines at the edges. The heads were cut above ground level They were weighed, extrapolated to per plot and multiplied by a factor of 0.8 in order to consider the reduced production at the edges. The results were extrapolated to Mg per hectare.

Statistical data analysis

The statistical differences in the Kimchi cabbage yield and soil chemical properties were determined by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by least significant difference (LSD) test.

Results and Discussion

Effects of fertilizers on Kimchi cabbage yield

After harvest in 2021, it was determined that Kimchi cabbage yield was highest under SRF treatment; though 10% higher than yield affected by CF, the yields were statistically similar. The control had between 30 to 38% significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower yield compared to the two fertilizer treatments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean Kimchi cabbage yields (Mg ha-1) in 2021 and 2022, as affected by the no fertilizer control, conventional fertilizer and slow release fertilizer. Different lower case letters attached to the means show significant differences between the treatment means.

| Treatments | Yield (Mg ha-1) | |

| 2021 | 2022 | |

| CF | 43.0 a† | 80.6 a |

| SRF | 48.0 a | 78.7 a |

| Control | 30.0 b | 16.8 b |

In 2022, fertilizer treatments significantly (p ≤ 0.05) affected Kimchi cabbage yield. Yields from CF and SRF were statistically similar; and about 78 - 79% higher than the control (Table 2). Nutrient supply from the CF and SRF increased Kimchi cabbage yield above the no fertilizer controls in both years. Overall, the yield by CF and SRF was not statistically different in both years.

Nitrogen content and uptake of Kimchi cabbage

The nitrogen content and nitrogen uptake by Kimchi cabbage was not significantly different in CF and SRF (Table 3). Therefore, there was no difference in nitrogen use efficiency by CF and SRF.

Table 3.

Nitrogen content and uptake of Kimchi cabbage for the year 2022 experiment.

| Treatment | Nitrogen content (%) | Nitrogen uptake (kg ha-1) |

| T-N | T-N | |

| CF | 4.0 a† | 220 a |

| SRF | 3.8 a | 194 a |

| Control | 1.7 b | 46 b |

Soil electrical conductivity

Averagely, soil electrical conductivity (EC) was higher in 2021 (0.32 dSm-1) than 2022 (0.24 dSm-1). There was no interaction (p > 0.05) between fertilizer treatments and sampling dates in 2021 (Fig. 2a), however, CF alone significantly affected (p ≤ 0.05) the highest EC (0.42 dsm-1) than SRF (0.29 dSm-1) and the control (0.25 dSm-1).

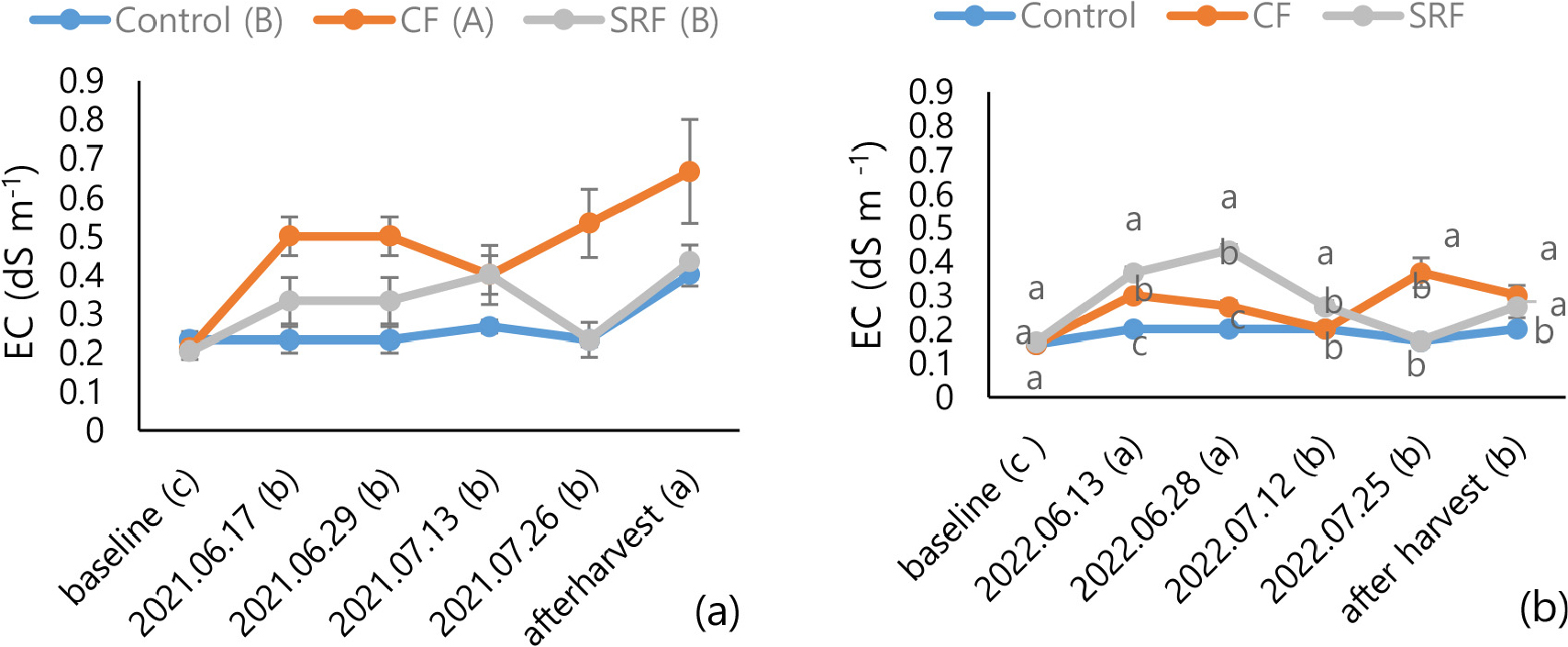

Fig. 2.

Changes in soil EC (y-axis) in response to CF, SRF and control applications in 2021 (a) and 2022 (b). The x-axis represents various sampling dates on which soil EC was determined in the Kimchi cabbage cultivation period. Error bars represent standard errors of the treatment means on each sampling date. Different uppercase letters attached to the legends show significant differences in average treatment means over the Kimchi cabbage cultivation period. Different lowercase letters attached to the sampling dates in 2021 and 2022 show significant differences in soil EC on various sampling dates. Different lowercase letters on the treatment means on each sampling date in 2022 (b) show significant differences in treatment means on specific sampling dates.

The lowest average soil EC was determined before transplant. There was a further significant decline just after Kimchi cabbage transplant and slight increases afterwards till harvest. The highest average soil EC was observed after harvest (Fig. 2). During the 2022 cultivation period, fertilizer treatments significantly interacted (p ≤ 0.05) with sampling dates to affect soil EC (Fig. 2b). The highest soil EC were observed the first two sampling dates after cabbage transplant; and SRF affected the highest EC’s (0.37 and 0.43 dSm-1) compared to CF and the control on both occasions (Fig. 1d).

Higher soil EC in 2021 than 2022 could be due to the low rainfall amounts received in 2021 compared to 2022. Soluble salts are more likely to accumulate and remain in the soil surface when less rainfall is received, compared to places that receive more rains where salts are highly leached beyond root zone (USDA, 2014). In both years, CF and SRF affected the highest soil EC (Figs. 2a and 2b) because fertilizers are predominantly salts, which increase the salt index of soil solutions and consequently the EC (Kamburova and Kirilov, 2008). Urea based fertilizers (like the CF applied in these studies) may cause more soil EC increases due to free release of NH3 from them (Laboski, 2019). Lower soil ECs were observed before transplant because fertilizers had not been applied at this stage, while soil EC increased again after harvest in 2021 because there was no nutrient uptake (Fig. 2a). Plants take up ions which are normally in the form of salts in the soil (IPNI, 2022).

Soil N (NH4+ and NO3-) concentration

Average soil NH4-N concentrations were lower in the field cultivated in 2021 (9.2 mg kg-1) than 2022 (17.8 mg kg-1). In 2021, the fertilizer treatments alone had significant effects (p ≤ 0.05) on average soil NH4-N concentrations (Fig. 3a) in the order: CF (16.9 mg kg-1)> SRF (4.8 mg kg-1) = control (5.5 mg kg-1).

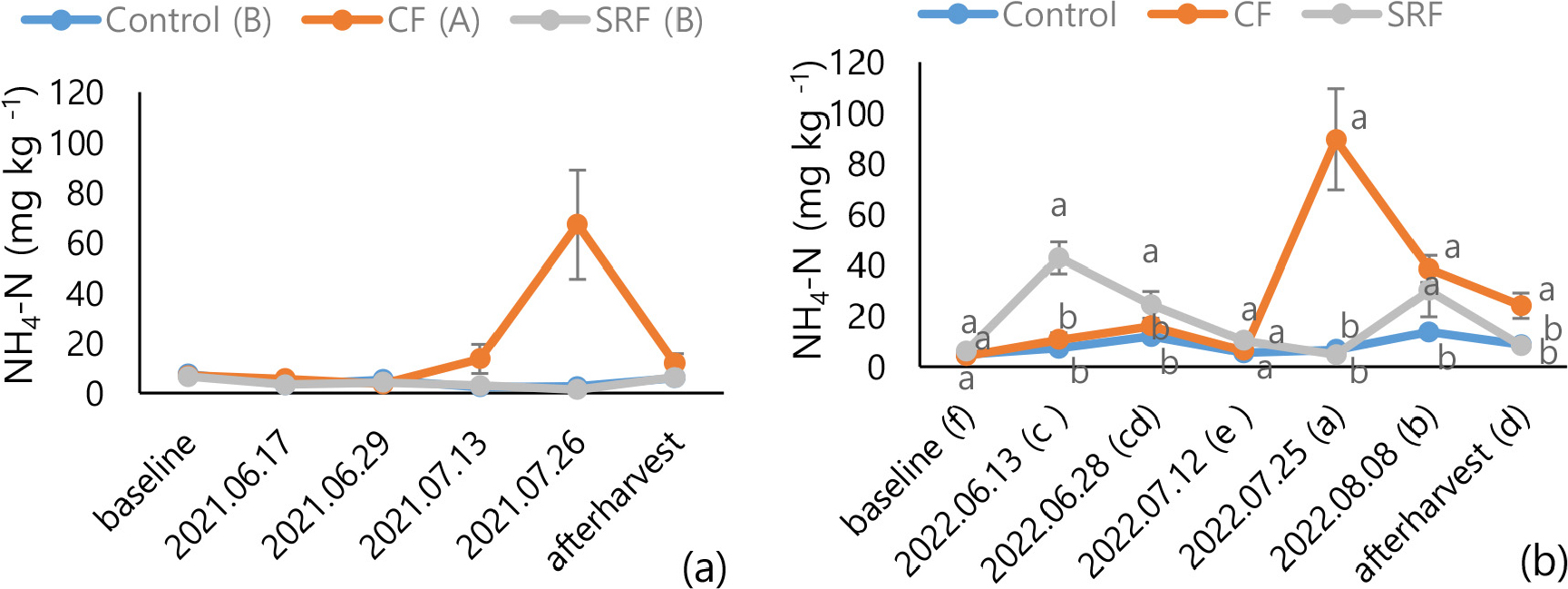

Fig. 3.

Changes in soil NH4-N concentrations (y-axis) in response to CF, SRF and control applications in 2021 (a) and 2022 (b). The x-axis represents various sampling dates on which soil NH4-N concentrations were determined in the Kimchi cabbage cultivation period. Error bars represent standard errors of the treatment means on each sampling date. Different uppercase letters attached to the legends show significant differences in average treatment means over the Kimchi cabbage cultivation period. Different lowercase letters attached to the sampling dates in 2022 show significant differences in soil NH4-N concentrations on various sampling dates. Different lowercase letters on the treatment means on each sampling date in 2022 (b) show significant differences in treatment means on specific sampling dates.

In 2022, there were significant interactions between fertilizer treatments and sampling dates, with the highest soil NH4-N concentration observed 4 weeks into cabbage growing season (2022/07/05) with CF affecting the highest concentration (89.6 mg kg-1) compared to SRF and the control on this date (Fig. 3b). SRF affected the highest soil NH4-N concentrations (6 - 43 mg kg-1) from before transplant until one month after cabbage transplant (Fig. 3b).

On average, soil NH4-N concentration was lower in 2021 than 2022 because the rate of NPK application in 2021 was about half that in 2022. Averagely, CF released the highest NH4-N throughout the growing season in 2021 (Fig. 3a) because it was a urea-based treatment. When urea is applied, it first reacts with soil water and soil urease enzyme to produce ammonium (Diaz, 2021). Thus, it is common to have high NH4-N concentrations in the soil, short periods after urea based fertilizer applications. Diehl et al. (2007) and Rochette et al. (2013) also found increases in soil NH4-N concentration, several days after the application of urea based fertilizers. In the same year, NH4-N release from both fertilizers and the control on all sampling dates were similar, though the full NPK rate was applied through SRF from the onset, because the mechanism of nutrient release from it is relatively steady (Geng et al., 2015). Higher NH4-N concentration from SRF at the initial stages of the growing season in 2022 (Fig. 3b) is only the result of higher NPK doses in 2022, relative to 2021 (Fig. 3a). Spikes in soil NH4-N concentrations from CF in the last week of July in both years (Figs. 3a and 3b) is commensurate with the second split application done in the prior week (second splits were applied in the third week of July). These spikes from CF on the second split application (though a lower NPK rate compared to SRF rate applied from the onset) were often higher than NH4-N released from SRF at any stage of the two growing seasons, indicating that NH4-N released from CF was rather rapid. Similar Kimchi cabbage yield affected by SRF and CF at the end of both experiments suggest that, a lot of the NH4-N released by CF was not utilized by the plants during the growing season, and may have been lost. Rochette et al. (2013) observed that a larger fraction of NH4-N is lost through NH3 volatilization with increases in urea based fertilizer applications. The downside to this is that, losses through NH3 volatilization is influenced by the increasing effect of the urea based CF on soil pH (Rochette et al., 2013); and the sudden temporary increase in soil pH could have adverse effects on growing crops.

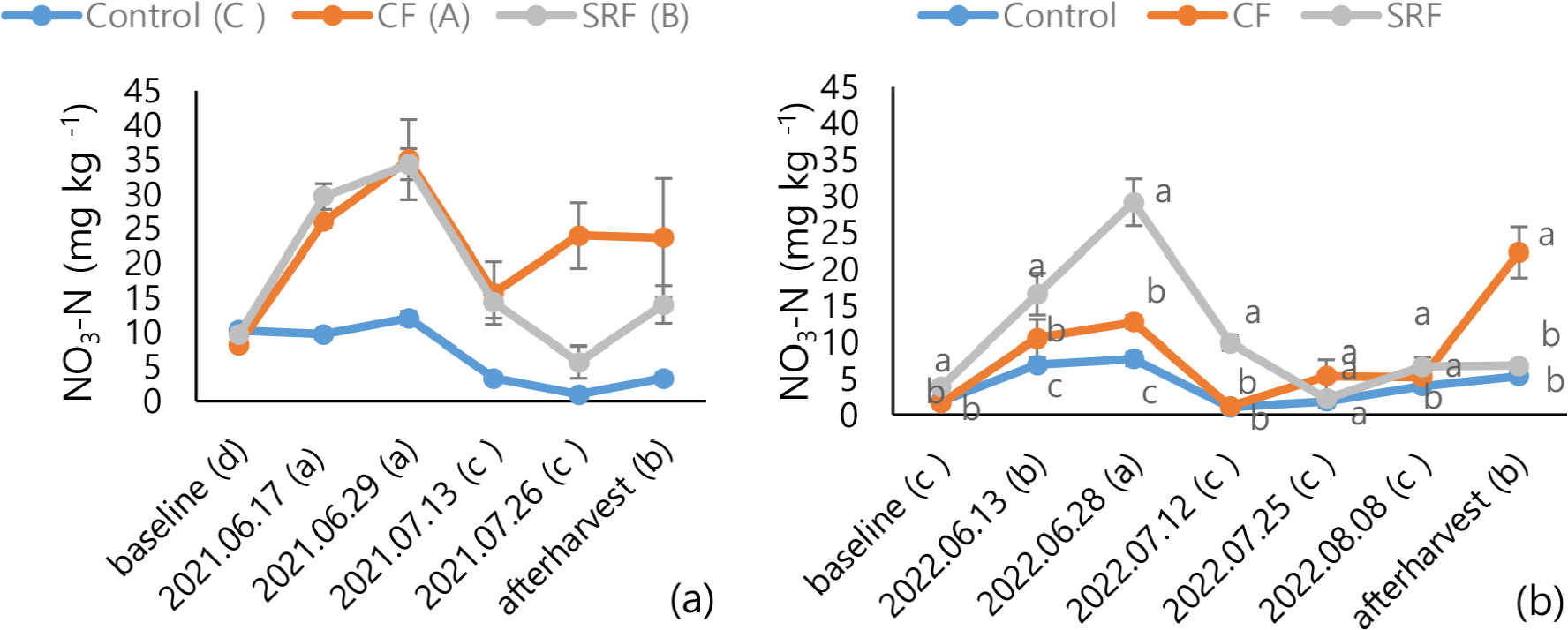

On average, soil NO3- concentration in the 2021 (13.8 mg kg-1) cultivated field was higher than in 2022 (7.8 mg kg-1). In 2021, fertilizer treatments alone had significant (p ≤ 0.05) effect on soil NO3- concentration in the order: CF (19.8 mg kg-1) > SRF (15.5 mg kg-1) > control (6.0 mg kg-1) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Changes in soil NO3-N concentrations (y-axis) in response to CF, SRF and control applications in 2021 (a) and 2022 (b). The x-axis represents various sampling dates on which soil NO3-N concentrations were determined in the Kimchi cabbage cultivation period. Error bars represent standard errors of the treatment means on each sampling date. Different uppercase letters attached to the legends show significant differences in average treatment means over the Kimchi cabbage cultivation period. Different lowercase letters attached to the sampling dates in 2021 and 2022 show significant differences in soil NO3-N concentrations on various sampling dates. Different lowercase letters on the treatment means on each sampling date in 2022 (b) show significant differences in treatment means on specific sampling dates.

Sampling dates alone also had significant (p ≤ 0.05) effect on soil NO3- concentration, with the highest average concentrations two weeks and one month after cabbage transplant (Fig. 4a). In 2022, there was significant interaction (p ≤ 0.05) between fertilizer treatments and sampling dates (Fig. 4b). SRF increased soil NO3- concentrations the first six weeks into the cultivation period (4.7 - 29.2 mg kg-1) above CF and the control (Fig. 4b). CF affected the highest soil NO3- concentration (22.3 mg kg-1) after harvest (Fig. 4b).

Nitrification is the process of biological oxidation of NH4+ to NO3- (Lehtovirta-Morley, 2018). The presence of soil NH4+ ions and oxidizing agents under aerobic conditions are important controls on the nitrification process (Sahrawat, 2008). The process is hastened under aerobic conditions (in the presence of O2 and other oxidizing agents; Choueiri et al., 2021); therefore, the higher soil NO3- concentration in 2021 (Fig. 4a) is the result of low rainfall amounts received in this year (Fig. 1) compared with 2022 (Fig. 4b). Low rainfall meant less soil moisture and more aerobic soil microsites, which favour the nitrification process. Since NH4+ is the substrate for the processing of NO3- in the soil (Juan-Diaz et al., 2022), it is in order that higher NH4+ in the soil under SRF application at the initial stages of the 2022 growing season (Fig. 3b) is translated to higher soil NO3- concentration around that same time (Fig. 4b). Increased soil NO3- concentration from CF at the end of the growing season in 2021 and 2022 (Figs. 4a and 4b) could be due to the increased soil NH4+ concentration after the second split. Soil NO3- processing after the second split CF application in 2022 (Fig. 4b) may have delayed until after harvest because of the largest rainfall amount received around that time (Fig. 1). Increase in soil moisture from the heavy rain received was likely associated with increases in anaerobic oxygen-deprived soil microsites (Brempong et al., 2019) which temporarily reduced the oxidation of NH4+ to NO3-.

Soil chemical properties after Kimchi cabbage harvest

After harvest in 2021, soil pH was the same (6.1; Table 4) among all CF, SRF and the control. It was comparable to the initial soil pH in 2021 (Table 1). After harvest in 2022, all three treatments maintained the initial soil pH (Table 1) again. In both year, EC had no statistical differences by CF and SRF.

Table 4.

Soil chemical properties after Kimchi cabbage harvest.

| Year | Treatment |

pH (1:5) |

EC (dS m-1) |

OM (g kg-1) | NH4-N (mg kg-1) | NO3-N (mg kg-1) | Av. P2O5 (mg kg-1) | Exch. cations (cmolc kg-1) | ||

| K | Mg | Ca | ||||||||

| 2021 | CF | 6.1 | 0.53 | 17 | 12 | 24 | 386 | 0.27 | 1.1 | 6.6 |

| SRF | 6.1 | 0.43 | 17 | 6 | 14 | 410 | 0.37 | 1.3 | 5.9 | |

| Control | 6.1 | 0.41 | 17 | 6 | 3 | 353 | 0.33 | 1.2 | 6.7 | |

| 2022 | CF | 6.1 a† | 0.30 a | 39 | 24 a | 22 a | 291 | 0.77 | 1.0 | 4.5 |

| SRF | 6.2 a | 0.27 a | 40 | 8 b | 7 b | 320 | 0.97 | 1.2 | 4.3 | |

| Control | 5.9 b | 0.20 b | 40 | 9 b | 5 b | 274 | 0.90 | 1.1 | 3.6 | |

After harvest in 2021, soil OM was maintained by all three treatments (Table 4) compared to the initial (Table 1) in both years. Soil NH4-N was highest under CF treatment, after harvest in 2021 (Table 4). It exceeded the initial concentration (Table 1) by 42%. The control and SRF maintained the initial concentrations (Table 1; Table 4). A similar trend was followed after harvest in 2022, with CF affecting the highest soil NH4-N concentration (Table 4). After harvest in 2021, both CF and SRF increased soil NO3-N concentration (Table 4) compared to the initial (Table 1), but concentration under CF was higher. Compared to the initial (Table 1), the control reduced soil NO3-N concentration by 63%. Soil NO3-N concentration was also highest under CF treatment after harvest in 2022 (Table 4). Soil available P2O5 concentrations had declined (Table 4) below the initial (Table 1) under all three treatments, after harvest in 2021. Among the three, SRF had the highest available P2O5 (Table 4). After harvest in 2022, both CF and SRF increased soil available P2O5 concentration (Table 4) above the initial (Table 1); and SRF was higher among the two. Soil K concentrations were lower compared to the initial (Table 1) among all three treatments (Table 4) after harvest in 2021. After harvest in 2022, SRF affected the highest soil K concentration, which was higher than the initial K (Table 1). Soil Mg concentrations were similar to the initial concentrations under all three treatments, after harvest in 2021 and 2022 (Table 1; Table 4). Compared to the initial (Table 1), all three treatments had reduced soil Ca concentrations after harvest in 2021 (Table 4). However, after harvest in 2022 (Table 4), CF and SRF maintained initial soil Ca concentrations.

The highest soil NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations were affected by CF after harvest in both years because CF releases nutrients faster than SRF (Liu et al., 2014). As a result, in a short period of time, following applications, soil applied with CF may have higher N concentrations than SRF. CF application is highly practical if nutrient leaching or immobilization are not serious concerns (Wolf, 1999), however under the condition being considered, thus after harvest, when plant uptake is minimal, higher N release from CF may translate to higher N losses, which may have dire environmental consequences (Li et al., 2018; Chandini et al., 2019). Decline in soil available P2O5 concentrations after harvest in both years may be due to the influence of soil pH on available P2O5 during the cultivation time. In both years, initial soil pH values were within peak available P2O5 availability range (5.0 - 7.0) (Hopkins and Ellsworth, 2005; Ros et al., 2020). It implies that under all treatment conditions, P release and uptake were highly effective, leaving little residue.

Conclusions

This two-year experiment was conducted to compare the effects of CF and SRF on soil chemical properties and Kimchi cabbage yield. It is part of an on-going research to gather information to make recommendations to farmers in the Highlands of the Gangwon State Government. NPK rates of 132:60:60 kg ha-1 were applied through the two fertilizers in 2021, while rates of 238:108:108 kg ha-1 were applied through the fertilizers in 2022. Soil NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations and soil electrical conductivity at various sampling dates were combined effects of the type of fertilizer (conventional or slow release), rainfall amounts received during the cultivation period in the year and the rate of NPK applied in the year. Averagely, it had the highest NH4+ concentration in 2021 and some sampling dates in 2022 because of the ammoniacal nature of urea, which was a part of the CF treatment mixture. It also left more NH4+ and NO3- residue in the soil after harvest, which may be tantamount to higher N losses and related environmental problems. Kimchi cabbage yield under both fertilizers were similar in 2021 (CF: 43 and SRF: 48 Mg ha-1) and 2022 (SRF: 79 and CF: 81 Mg ha-1). Similar yields from the two fertilizers irrespective of higher nutrient release from CF most of the time, supports that CF could be subject to larger losses than SRF. Moreover, it is less laborious to apply SRF because only a single application is required while split applications are required for CF application. Based on information gathered in these experiments, SRF may be recommended. However, other factors of production such as the costs of fertilizers and availability should be considered in the continuous research works.